Bruce Springsteen released a new song yesterday titled “Streets of Minneapolis.” It directly addresses the ongoing immigration raids and subsequent protests in that city, to include the killings of Renée Good and Alex Pretti. As is always the case when Bruce comments on politics and current events, the song is getting tremendous attention online. And as I said in a recent post about Bruce’s political comments during his Light of Day performance, such actions are nothing new for Bruce. He has been using his music to advocate for causes he believes in even before his first albums with Columbia; before the formation of the E Street Band.

One of his earliest songs, “All Man the Guns,” was written when he was still a teenager. As Bruce recalls, “it was an anti-war song I wrote at probably 18 or 19 years old,” during the Vietnam War (a conflict during which close personal friends of Bruce’s were killed). These are the oldest handwritten Springsteen lyrics preserved in our Bruce Springsteen Archives. And it is our job at the Bruce Springsteen Center for American Music to document, interpret, and contextualize Bruce’s comments and actions, across the long arc of his career.

Towards that end: Springsteen’s remarks fit within a long American tradition in which artists across the political spectrum have used music to advocate for causes they believe in. From folk singers and soul artists aligned with labor and civil rights movements, to country musicians voicing patriotism, religious conviction, or skepticism of centralized government power, popular music has always served as a platform for civic expression. These interventions are not anomalies or recent inventions; they are woven into the fabric of American music history itself. Artists have used songs, stages, and public appearances to reflect their values, rally communities, raise funds, and, at times, provoke disagreement. Whether listeners embrace or reject the message, the act of musical advocacy has consistently been part of how artists engage with the world beyond the studio and the stage.

Musical advocacy will actually be the theme of the first exhibit in our rotating gallery when we open the new home of the Springsteen Center this Spring. That exhibit, Chimes of Freedom: Protest, Politics, and the Power of Song, explores how music has shaped and reflected social awareness throughout American history. It traces music’s enduring role as a force for education, expression, and change across generations and genres—from the spirituals sung by the enslaved, to the patriotic tunes of the American Revolution, to the powerful anthems that energized the Civil Rights Movement of the 1960s, to today’s musical calls for racial, social, and economic justice.

We’ll examine songs like:

“Yankee Doodle” (c. 1760s–1770s)

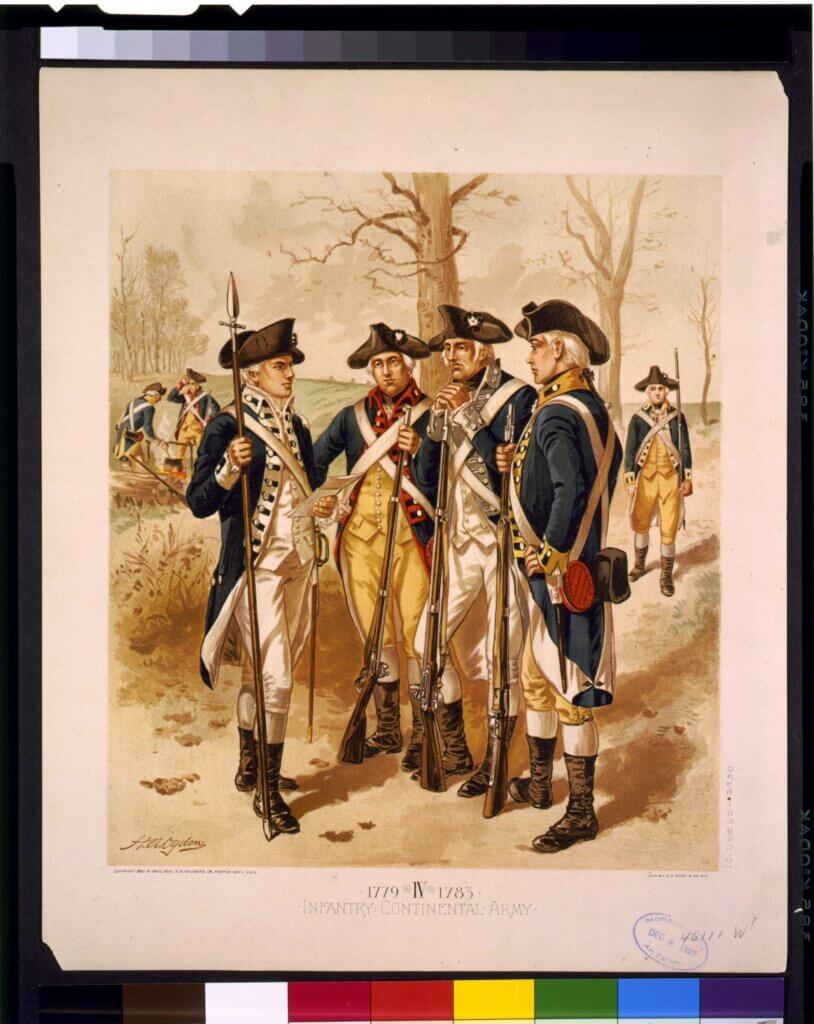

Originally sung by British troops to mock colonial militias, “Yankee Doodle” was quickly reclaimed by American revolutionaries and transformed into a song of defiance and pride. Lines referencing a “Yankee Doodle dandy” reflect how ridicule was inverted into identity, as music became a tool for morale-building and political solidarity during the American Revolution.

Infantry, Continental Army. Courtesy Library of Congress.

“The Battle Hymn of the Republic” (1861)

Written during the Civil War by Julia Ward Howe, “The Battle Hymn of the Republic” fused religious imagery with political purpose, framing the Union cause as a moral struggle. With references to a truth that is “marching on,” the song drew on biblical language to inspire resolve and righteousness among its listeners. Widely adopted beyond its original context, it demonstrates how music has long been used to link national conflict, faith, and ideals of justice—illustrating the powerful role songs can play in shaping how Americans understand war, sacrifice, and moral duty.

“Over There” (1917)

Written by George M. Cohan after the United States entered World War I, “Over There” became one of the most popular American songs of the era, urging young men to enlist and support the war effort. With its repeated call to send “the word” overseas, the song reflects how music was mobilized as a tool of patriotism, morale-building, and national unity during wartime. Its widespread circulation demonstrates the role of popular music in shaping public sentiment and encouraging civic participation during moments of global conflict.

The Fort Monmouth, NJ band practices “Over There.” Courtesy US Army / Melissa Ziobro.

“Which Side Are You On?” (1931)

Written during a coal miners’ strike in Kentucky by Florence Reece, “Which Side Are You On?” became one of the most enduring songs of the American labor movement. With stark lyrics that demand moral choice, the song reflects how music has been used to organize workers, build solidarity, and frame labor struggles as questions of justice and dignity.

“Deportees (Plane Wreck at Los Gatos)” (1948)

Woody Guthrie wrote “Deportees” in response to the 1948 plane crash in Los Gatos, California, which killed 28 Mexican farm workers being deported from the United States. With lyrics emphasizing the namelessness of the victims—“Some of us are illegal, and some are not wanted / Our work contract’s out and we have to move on”—Guthrie’s song highlights labor exploitation and social invisibility. It exemplifies how music can bear witness to injustice and give voice to marginalized communities, turning a tragic event into a call for awareness and empathy.

“Blowin’ in the Wind” (1962) – Bob Dylan

Bob Dylan’s “Blowin’ in the Wind” poses a series of rhetorical questions about peace, freedom, and human rights, such as “How many times must a man look up / Before he can see the sky?” The song became a defining anthem of the Civil Rights Movement, illustrating how popular music can raise moral and political questions, spark reflection, and inspire social engagement without offering explicit answers.

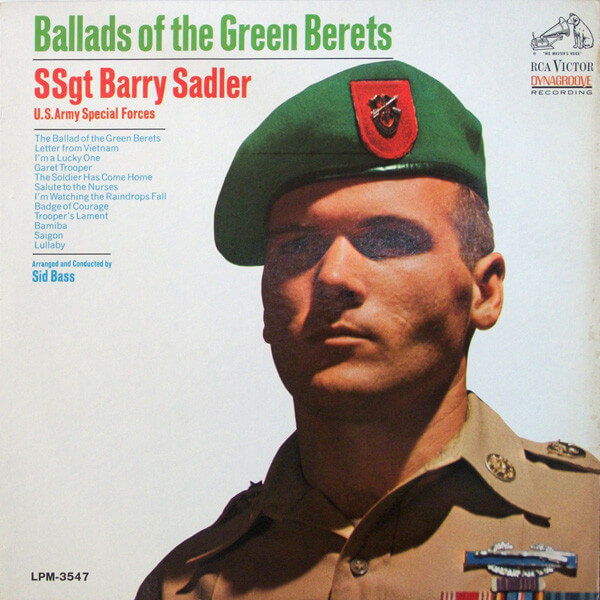

“The Ballad of the Green Berets” (1966)

Written by Barry Sadler and Robin Moore during the Vietnam War, this song offered a patriotic tribute to U.S. Special Forces, praising soldiers who are “trained to live off nature’s land” and to “fight when called.” Hugely popular upon release, it illustrates how music has also been used to affirm military service and national purpose during moments of political division and war.

“WAR” (1970) – Edwin Starr

Originally written for Motown by Norman Whitfield and Barrett Strong, Edwin Starr’s “WAR” became a fiery protest song against the Vietnam War. Its direct refrain—“WAR, what is it good for? Absolutely nothing!”—captures widespread frustration and anti-war sentiment in the United States. The song demonstrates how music can serve as both a rallying cry and a cultural barometer of dissent during times of national conflict.

“Big Yellow Taxi” (1970)

Joni Mitchell’s song captured growing environmental consciousness in the late twentieth century, lamenting development and ecological loss. With its memorable refrain about paving “paradise,” the song reflects how popular music helped bring environmental concerns into mainstream cultural conversation.

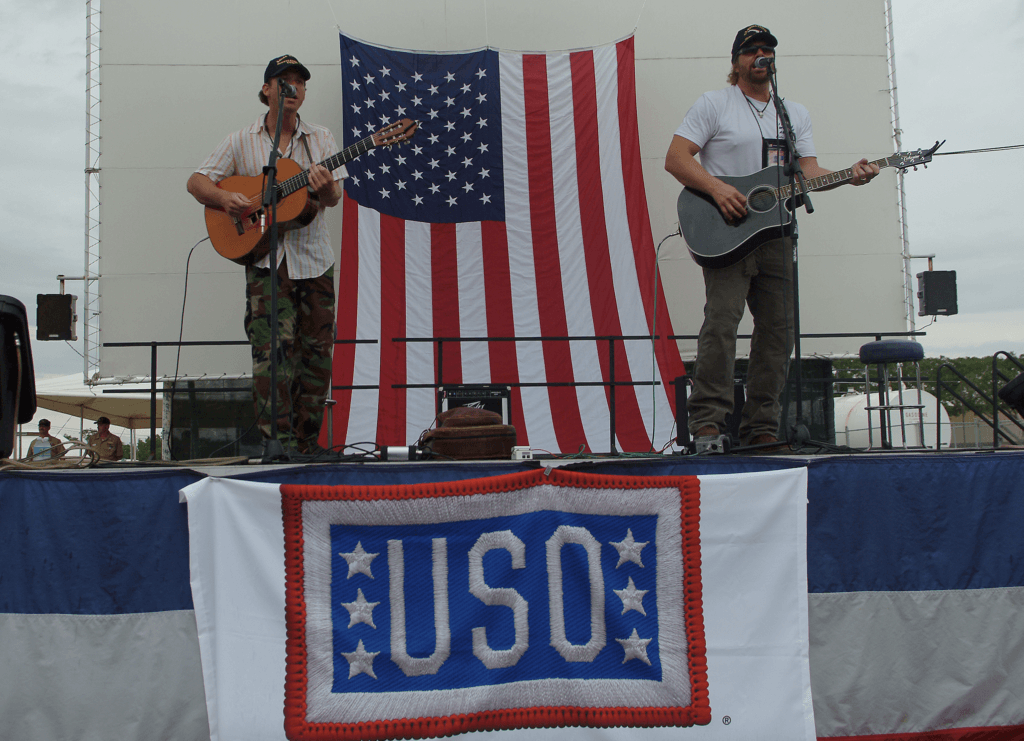

“Courtesy of the Red, White and Blue (The Angry American)” (2002)

Written in the aftermath of the September 11 attacks, Toby Keith’s “Courtesy of the Red, White and Blue” channels grief, anger, and defiant patriotism. Referencing the flag and warning that “you’ll be sorry that you messed with the U.S. of A.,” the song reflects a moment when music became an outlet for national mourning and resolve. Its popularity underscores how artists have used music to express solidarity, vengeance, and patriotic identity during times of crisis, even as such expressions sparked debate about nationalism, militarism, and dissent.

Toby Keith performs for service members, 2005. Courtesy Wikimedia.

“Born This Way” (2011)

Lady Gaga’s “Born This Way” explicitly affirms LGBTQ+ identity and self-acceptance. Its mainstream success underscores how messages that once circulated at the margins of popular music increasingly moved into the cultural center.

New York City Pride Parade, 2018. Courtesy Wikimedia.

And now, of course, we’ll add a discussion of “Streets of Minneapolis,” as the latest entry in a 250-year history of American musicians using their voices to respond to moments of crisis, conflict, and change. The song becomes a primary source document via which future generations can analyze, and form their own opinions on, the events of 2026, with lyrics like:

Oh our Minneapolis, I hear your voice singing through the bloody mist

We’ll take our stand for this land and the stranger in our midst

Here in our home they killed and roamed in the winter of ’26

We’ll remember the names of those who died on the streets of Minneapolis

Whether the songs, artists, and themes we will cover in Chimes of Freedom express protest, patriotism, grief, or resolve, they reveal how deeply music has been intertwined with public life in the United States. By placing Springsteen’s latest work alongside earlier examples—from revolutionary anthems to wartime ballads—the exhibition invites visitors to consider not only what artists say, but why music has remained such a powerful vehicle for civic expression across generations.

Melissa Ziobro

Director of Curatorial Affairs

Bruce Springsteen Center for American Music

Monmouth University

January 29, 2026